The British public generally view aid as a positive thing. This is repeatedly evidenced by research and by additional public giving during specific campaigns – from the outpouring of public generosity for victims of the Tsunami to Comic Relief, which have raised hundreds of millions of pounds.

However, many are unhappy with the increase in our aid budget, especially at a time of austerity and when the highest number of food packages – over a million in the 2014 to 2015 financial year – have been given out by food banks here in the UK.

On the surface, it’s a reasonable and natural position to take.

But this position sits within a context of widespread misconceptions about our aid budget and a lack of genuine propositions put forward for its purpose.

The misconceptions

- We are spending too much on aid

According to an Ipsos Mori poll, over a quarter of the British public believe aid is one of the top three items among Government spending. In reality, although the budget has seen an increase, it is still only about 1% of Government spend (or 0.7% of Gross National Income). Nevertheless, many more than a quarter of us believe it is significantly higher than it really is.

We’re not alone.

In the US, the average estimate of the aid budget across the public is that it constitutes a massive 28% of Federal spending. But again, in reality, it is also about 1%. Interestingly, although it remains the one budget line that most people favour cutting, when asked if the aid budget was only 1% would they then favour cutting it, 28% said this would be too small an allocation to aid and 31% said that this was about the right amount. The majority are in favour of 1%.

Perhaps the lack of awareness of the actual proportion of the budget spent on aid is at the source of people’s unhappiness with the increase in the allocation to it.

- Aid is ineffective

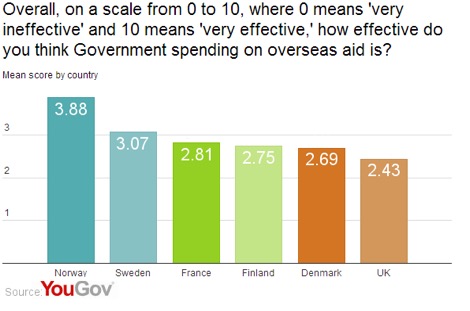

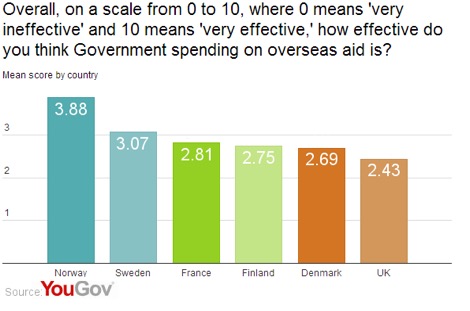

A YouGov poll across a number of European countries suggests the misgivings we have about aid might be rooted in perceptions that it is ineffective, with the British being the most sceptical.

But to what extent is this due to a lack of widespread awareness of what aid actually achieves?

Mark McGillivray’s paper for the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) states the “overall message from the empirical literature is thus reasonably clear: to the extent that growth is good for poverty reduction, it can reasonably be inferred that poverty would be higher in the absence of aid flows.”

Adjusting for the growth that China was already experiencing, extreme global poverty was reduced by a third between 1990 and 2008. It is even less now, in no small part as a result of aid. And within all this there have been great leaps made in saving and positively transforming the lives of millions of people around the world. For example, we have seen a substantial decrease in child mortality from 11.7 million in 1990 to 6.8 million in 2011, and this is in the face of an increasing global population. Much of this kind of success is verifiably attributable to the deployment of aid through its support of health and other initiatives. There really is some great news on aid effectiveness. Have a quick look at some of the results posted by the Department for International Development (DFID).

Of course, not all aid is effective. And there is widespread recognition that aid must continue to improve its effectiveness. With this in mind, there is a great deal of work invested in seeking to improve the performance of aid, most recently in locking in the commitment of over 160 governments to five principles: ownership, alignment, harmonisation, mutual accountability and results. The commitment at the heart of these principles is to ensuring support for developing countries to strengthen their institutions and grapple with corruption.

But here’s a question. Would we reduce health and education budgets on the occasions those services are not as effective as they should be? When aid doesn’t work we need to review the polices behind it and improve them.

- Most aid is lost to corruption

Corruption lies at the heart of the root causes of poverty. Cultivated by poor governance, weak institutions, low wages and a complex array of other factors, it denies people living with poverty access to fundamental services, food and medicine. It is ugly and it is an injustice.

And there is no doubt corruption is a serious problem to the aid sector.

But we can’t cherry pick the well-run countries to send our aid to. The people living with the most extreme poverty often live in countries where levels of corruption are high. This is the business end of the stick. And it’s bloody difficult.

Just because something is difficult does not mean we shouldn’t do it. We need to invest more in the capacity of DFID to undertake the research and pilot schemes to improve our ability to successfully forge development partnerships in these very challenging environments.

In the meantime, a significant proportion of aid is actually invested in building stronger institutions, helping to improve governance and in tackling corruption head on in many of these countries.

And a large amount of aid does exactly what it is intended to do. Robust processes are in place to undertake thorough due diligence on NGOs like Hope and Homes for Children, so funders like DFID can be confident that money is well managed and used to deliver world class projects. Most NGOs like ours will not fund governments nor offer bribes. We use the money we receive in the interests of the children we exist to serve and we can prove it.

So while recognising that there is a challenge, we also really do need to avoid exaggerating it. Our energy is better spent trying to overcome it.

- Charity begins at home

The need for the distribution of one million food packages to families in the UK who cannot afford to feed themselves is not a consequence of allocating 1% of the national budget to aid. It is the consequence of inadequate Government social and economic policy. The UK remains one of the richest countries in the world and the injustice of people not being able to feed their families is derived from the inequality in our society more than anything else.

Yes, charity does begin at home. But the reasons for the need for charity at home will be left unaddressed if we cloak them with the increase in the aid budget. And let’s face it, the world is shrinking. Are we really so isolationist in our perceptions of ourselves? We are increasingly globalised citizens. The world is our home.

So what are the reasons why our aid commitment should have been increased?

A number of reasons have been put forward, not least by politicians in the run up to the elections. These range from the benefits of aid in helping to reduce the threat of terrorism, through reducing immigration, to enhancing our diplomatic clout around the world. But there is very little evidence that aid actually achieves any of these things.

Here are four reasons why we should stick to our increased aid allocation and continue to protect it.

- Aid has a great value proposition

As aid increases it can deliver very significant economies of scale.

For example, as the US Government’s programme to combat HIV/AIDS (PEPFAR) was scaled it achieved a reduced cost per patient from $1,053 to $339. The Anti Retroviral Therapy it has supported is estimated to have saved 6.6 million lives between 1995 and 2012 and reduced the risk of transmission by 96%.

In making a significant contribution to addressing the AIDS pandemic as a global public health threat, this kind of aid programme has reduced the overall cost of care and has enabled millions of people to contribute to, rather than depend upon, their economies. The economic returns on the investment through increased labour productivity, reduced medical care and so on are variously estimated between 81% and 287%.

- Aid is a vital component in the suite of responses to global issues that will affect us all

There are a number of global issues that threaten us all. Think Ebola. Try containing and responding to subsequent outbreaks without significant aid commitments.

And here’s another one. The funding required to address the impact of climate change in developing countries is massive. Aid has a critical role to play in enabling developing countries to adapt to climate change.

Climate change is a global phenomenon. It will in time affect everyone and it will affect us all differently. Depending on their location some people will experience much drier conditions, some wetter, some hotter and some colder. And many will experience increased variability across all these weather patterns, including greater occurrences of extremes.

Arguments have been made which suggest that developed countries will be least vulnerable to climate change, in no small part because of our ability to adapt to it. Almost everyone agrees the brunt of the impact will be felt in developing countries

This impact will range from mass public health challenges, including increases in respiratory and water borne diseases, through to widespread problems with food security. Public health and food security problems in developing countries pose a significant threat to developed countries, many of which are (or will be) net food importers. If developing countries can’t produce the food they need – and cheaply – because of climate change, then we all have a problem.

Because climate change occurs through the global meteorological system it can only be effectively tackled through global agreements and action. One country on its own cannot address it.

This is why international aid instruments are so important.

Aid funding has a very important role to play in addressing the impact – direct and indirect –climate change will have on all of us. Climate change is, largely, the consequence of approaches to development that are proving unsustainable.

So using aid to invest in developing countries to underwrite the risk associated with experimenting and finding new development pathways must be a priority in order to ensure that the causes of climate change do not compound the problem. This kind of investment will create the conditions in which local, national and international trade will have an improved chance to develop economies in a way that they can cover increasing proportions of the cost of adaptation for themselves.

But not all aid enables adaptation and nor should it (in the case of humanitarian support for example). Nor is all adaptation necessarily development: the costs of adaptation are more the province of political agreements and structural funding mechanisms than of aid.

Indeed, the costs of adaptation are enormous. The United Nations Development Programme estimates the global annual costs of dealing with the consequences of climate change are of the order of magnitude of $100 billion. And the longer it takes to negotiate and begin implementing global agreements at this scale, the more rapid will be the increase in the costs of dealing with the impact of climate change.

It is not for aid budgets to meet these costs directly, but aid does need to be of a scale to leverage adaptation funding as it comes on line. For example, aid can be used to pilot adaptation initiatives throughout development programmes in a way that presents new approaches that are scalable.

In the long run, the value of an increased aid budget that can achieve this kind of leverage will not only reduce the indirect impact to developed nations of increasing public health and food security challenges (among others) in poorer countries, but it will reduce the suffering and the increasing costs of dealing with it over the long term.

- Aid is not largesse. It is our obligation.

It doesn’t matter which way you look at the growing cost of human suffering derived from climate change in developing countries, we are responsible for it. Europe. The US. All industrialised countries.

We continue to enjoy the benefits of being an industrialised economy. The consequences of this growth can be summarised by the increase in the levels of the of the three main greenhouse gases:

- Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide concentrations have increased by almost 40% since pre-industrial times. The current Carbon Dioxide level is higher than it has been in at least 800,000 years.

- Methane is more abundant in Earth’s atmosphere now than at any time in the past 650,000 years. Concentrations are now more than two-and-a-half times pre-industrial levels.

- Concentrations of Nitrous Oxide have risen by approximately 18% since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

It is people living in developing countries who will have to deal with the destructive impact of the industrialisation of our economies. With more than half of humanity living in developing countries then many will suffer at our expense.

So if a proportion of increased aid funding to 0.7% of GNI from developed countries can play a critical role in leveraging the capacity to enable the majority of humanity to adapt to climate change, then these are pretty modest wages to pay for our own “developed” status and comfort.

- Future proofing

There are 2.2 billion children in the world. A quarter of humanity. Looking to the future, the majority of children will be born into developing countries.

Local authorities and governments in these nations struggle to find enough funding to provide for the basic rights of children to education and health and they allow or rely on damaging approaches to care and protection (see Hope and Homes for Children website). We cannot wait for one or two generations for their economies to develop.

If we do not help to address poverty in these countries now, the problem will be transmitted from one generation to the next with growing consequences for developed countries. And injustice will be at the centre of the inter-generational transmission of poverty, with conflict as its consequence.

If we view aid as an issue for the present only, then we are not seeing its value in the round.

We need to reframe how we see our aid contributions with the language of investment and a focus on the value of what we are paying for. And the legacy of this for future generations.